- Published on

How Global Economies Built Thriving Commercial EO Industries

Preamble

This is the second part of a three part series I am writing to understand the commercial EO landscape in Africa. Be sure to read Part 1 before moving on.

Introduction

In his thought provoking article "Africa's Unfair Advantage: How Late Adoption fuels innovation and technology," Kayode challenges conventional thinking by reframing Africa's delayed technological adoption as an asset rather than a liability. He argues that by bypassing outdated legacy systems, African nations can adopt cutting-edge solutions directly, enabling technological leapfrogging.

This perspective aligns with Peter Thiel's critique (or my interpretation of it) in "Zero to One," where he questions the language often use to describe global development. Thiel argues that labeling nations as "developed" versus "developing" wrongly implies that advanced economies have reached an endpoint of innovation. This distinction overlooks the vast potential for building new innovations on existing foundations, as development is an ongoing process rather than a closed loop.

Both thinkers converge on a powerful insight that is worth noting, the idea that starting late doesn’t necessarily mean falling behind. In fact, it can offer a strategic advantage allowing to begin with greater knowledge, more advanced tools, and fewer established constraints.

The next part of this article explores the evolution of the commercial Earth Observation (EO) industry in two major global economies. From the policy experiments that failed to account for market readiness, to the heavy infrastructure investments that lacked local context, we can extract valuable lessons for Africa's emerging commercial EO sector. History is now our tool for building a better future. As Santayana famously noted, "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”* But those who do remember it and study it well can do something better.

United States: Policy, Risk, and the Rise of a Commercial EO Market

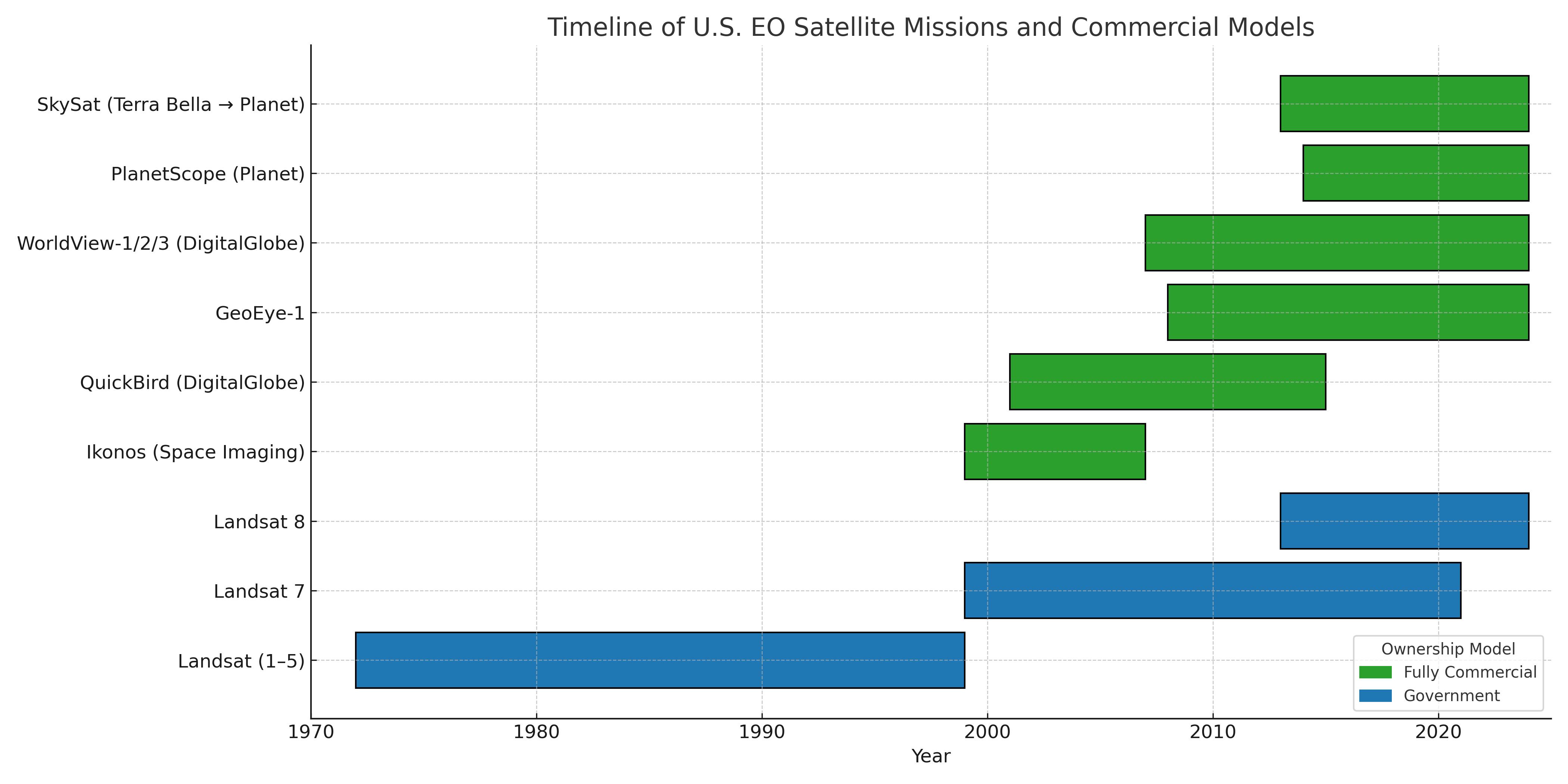

The commercialization of Earth Observation (EO) in the United States had an awkward beginning. It started in the early 1980s, when the U.S. government attempted to privatize the Landsat program, a long-term civil EO initiative launched by NASA in the 1970s. While the program began as an experimental effort, it quickly became operational as agencies like the Department of the Interior (DOI) found its satellite imagery useful. Hoping the private sector could manage the program more efficiently, Congress passed the Land Remote Sensing Commercialization Act of 1984, which established legal authority for private firms to operate, maintain, and sell EO data. Under this act, the Earth Observation Satellite Company (EOSAT) was granted the right to operate Landsat-4 and Landsat-5, manage data distribution, and lead the development of future satellites in the series.

But the market wasn’t ready. The technology was expensive, infrastructure was lacking, and demand was minimal. By 1992, it was clear the privatization had failed. In response, Congress passed the Land Remote Sensing Policy Act which re-established Landsat as a government-owned, publicly funded program. But crucially, it left the door open for private firms to still operate in the market. This was reinforced by Presidential Directive 23 (1994) under the Clinton administration, which formally authorized private firms to build and operate their own high-resolution imaging satellites up to 1-meter resolution for the first time.

Space Imaging Inc. keyed into this new policy direction and, in 1999, launched IKONOS, the first commercial satellite to provide high-resolution optical imagery to the public. Though the commercial EO market was still in its infancy, IKONOS launched with the expectation and strong signals that U.S. government policy would back them. Through agencies like NIMA (now the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, NGA), the government stepped in as an anchor customer, making firm commitments to purchase data. This strategy was part of a broader “buy commercial first” policy, where the government opted to procure EO data from private providers rather than build its own satellites, unless absolutely necessary. This also led to the creation of programs like the Next View and Enhanced View where funds came in for private organizations to build satellites. This approach helped stabilize early commercial ventures and laid the groundwork for a growing industry.

Still, throughout the 2000s and into the early 2010s, the commercial EO ecosystem continued to develop with new satellites like QuickBird (2001), WorldView-1 (2007), Geoeye-1 (2008), WorldView-2 (2009), WorldView-3 (2014) entering the market. However, commercial imagery was still expensive, and the ecosystem for scalable, downstream services wasn’t mature. As a result, few startups existed that could build directly on the data. Most commercial EO companies also generated revenue through partnerships with foreign governments that couldn’t afford their own EO infrastructure, as well as with large enterprises and mapping firms. The high cost of imagery, along with other limiting factors such as unclear data distribution policies constrained the growth of the startup scene.

A turning point came with the opening of Landsat data in 2008, which dramatically lowered the barrier to entry. Now startups, researchers, NGOs, and small companies could access free, high-resolution imagery. This led to an explosion in analytics and value-added services (VAS) for crop monitoring, deforestation alerts, urban growth mapping, and more with agencies now funding downstream layers. Many early-stage Earth Observation (EO) startups in the U.S. received funding from government agencies, particularly through Small Business Innovation Research programs and research-related contracts from NASA, NOAA, the DoD, and NSF.

This foundation of public funding and strategic procurement helped de-risk the EO sector and validate its potential. EO Companies could mature their technology and prove real world value. As the market evolved and as technologies like cloud computing and APIs made EO data more accessible, the commercial potential of EO became increasingly clear. This shift caught the attention of venture capital firms. By the early 2010s, VC firms began recognizing that EO could bring in some more values. Companies like Planet Labs, Descartes Labs, and Orbital Insight were among the first to attract serious venture funding, reframing EO as a data business and a scalable, high-growth tech opportunity.

Source: Author

Europe: Public Infrastructure and the Path to Market Maturity

Europe’s EO journey followed a different path, with earlier commercialization and stronger institutional integration.

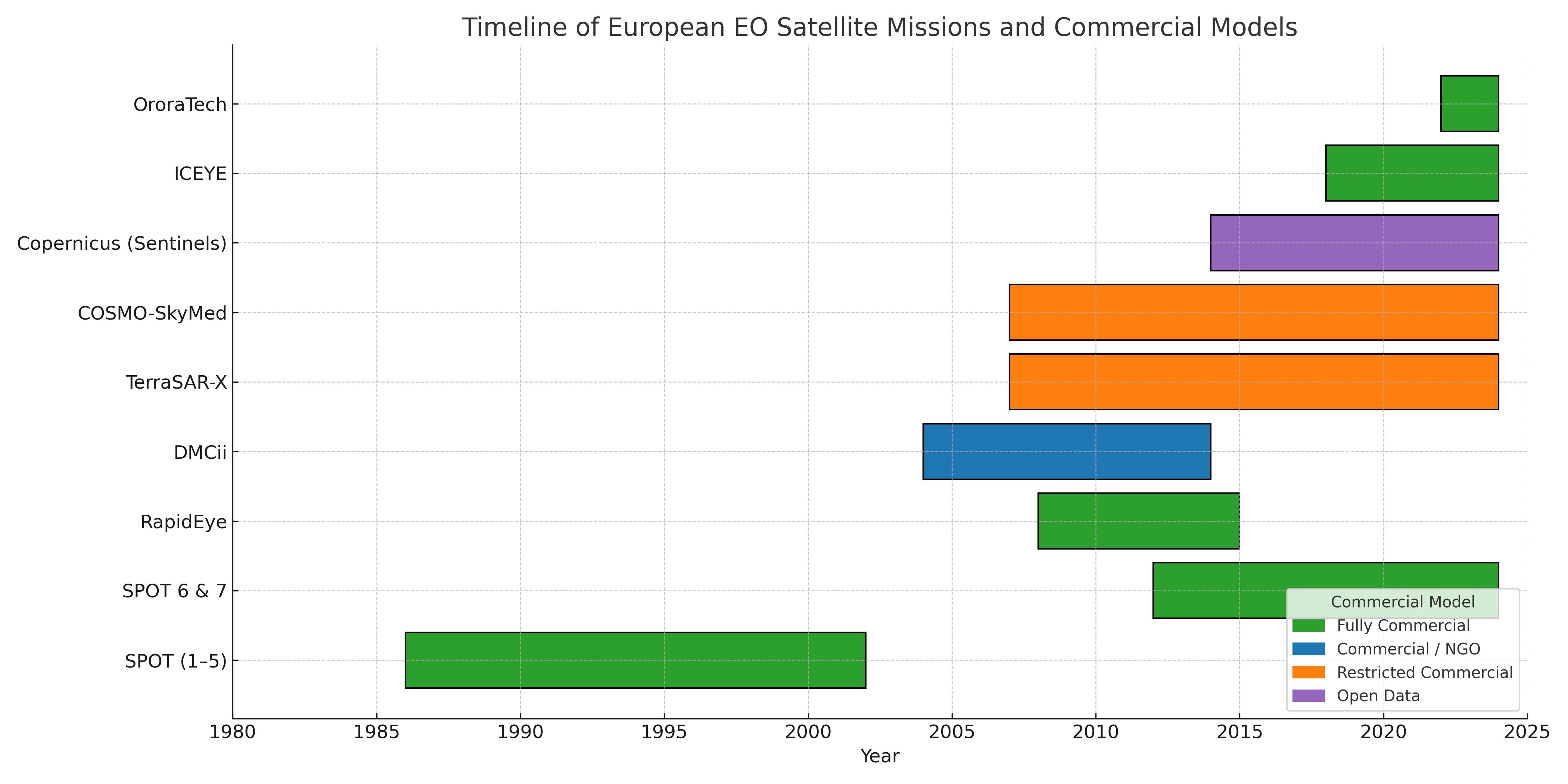

In the 1970s, CNES (Centre National d'Études Spatiales), the French space agency, developed the SPOT program — the first European Earth observation satellite initiative. Although SPOT was a state-backed institutional project, it also had a commercial component: Spot Image, a public-private company tasked with selling and distributing SPOT imagery worldwide. Spot Image was among the first companies globally to commercialize EO satellite imagery and became one of the earliest commercial EO success stories in Europe.

For decades, Spot Image dominated the commercial EO market in Europe. But by the early 2000s, new players began to enter, often supported by government funding or research institutions. These included new satellites like Disaster Moninoting Constellation in 2002, TerraSAR-X in 2007 by DLR, Germany, COSMO-SkyMed in 2007 by the Italian Space Agency, Italy, RapidEye in 2008, Germany,among others. Despite these additions, the high cost of data limited the growth of the commercial EO sector in Europe during this time.

The true commercial breakthrough came after 2010, driven largely by the launch of the Copernicus program, developed by the European Space Agency (ESA). Copernicus was a direct evolution of GMES (Global Monitoring for Environment and Security), an initiative launched in the 1990s to give Europe an independent and integrated Earth observation capability. GMES laid the policy, technical, and organizational foundation for Copernicus, which would go on to become the world’s most advanced open EO data program. Before Copernicus, Europe depended heavily on U.S. Landsat data for imagery, but SPOT helped prove that Europe could compete and that EO could support sectors like climate monitoring, agriculture, and crisis response.

Prior to Copernicus, scaling EO analytics was difficult. Only a few players such as university labs, NGOs, and consultancies could afford to work with limited and expensive data. Most analytics were developed for institutional clients like ESA, national governments, or multilateral organizations such as the World Bank. The opening of Sentinel data under Copernicus changed everything. The availability of large volumes of high-quality, free EO data created the conditions for scalable business models. This led to a startup boom across Europe, with companies offering analytics platforms, decision support tools and SaaS products.

Government-backed funding programs soon followed to accelerate this growth. These included ESA Business Incubation Centres (BICs) in 20+ locations across Europe, offering grants, mentorship, and technical access to EO startups. Additional initiatives like the Copernicus Accelerator, Copernicus Masters, and Horizon 2020 further supported commercial innovation and helped bridge research with market-ready applications. This momentum also encouraged the rise of next-generation EO companies building their own constellations, backed by venture capital. A prime example is ICEYE, which has launched a commercial SAR (Synthetic Aperture Radar) constellation, OroraTech, a Munich-based startup focused on wildfire detection and climate monitoring, which launched its first thermal infrared sensor into orbit in 2022.

Today, Europe has lots of EO-related startups and SMEs, with the EO market projected to expand from €3.4 billion in 2023 to almost €6 billion by 2033 according to the EUSPA

Source: Author

Lessons for Africa’s Emerging Commercial EO Ecosystem

The rise of the commercial Earth Observation (EO) sector in these leading economies holds several valuable lessons for Africa not just in how EO infrastructure is built, but in how it's nurtured, governed, and scaled into an economic and social asset. These efforts were the result of a deliberate and strategic convergence of several key forces including government support, regulatory policy, open data access, and technological innovation. Each played a foundational role in shaping the modern EO landscape as we know it today.

The first and perhaps most critical lesson is the importance of strong government leadership and policy direction. African governments and regional institutions like the African Union can serve as both early funders and anchor customers for EO data and services. Public procurement of EO analytics and insights tailored to local use cases can create stable demand and reduce business risks for EO startups. This approach can be replicated by making EO data and services central to procurement strategies across ministries. This is especially important in areas where national or regional EO capacity is still developing. With the right public-sector demand, this strategy can fuel the emergence of startups and build the foundation for a vibrant, investment-ready EO market.

While existing open data provides a valuable foundation rather than a complete solution, it offers African startups an entry point into the downstream segment of the Earth Observation value chain like delivering analytics, insights, and decision-support services. Africa is already benefitting from global open data like Landsat and Sentinel, but there’s still room to go further by localizing access and building platforms that can support multiple sectors. With technology playing a catalytic role in scaling this opportunity, as it did in the global economies, access to computing and advanced analytics now enables satellite data to be processed more efficiently. Startups can begin to use AI to automate analysis and make data more easily accessible.

Several successful startups in both the U.S. and Europe began by leveraging open EO data, especially from Landsat and Sentinel, before moving into more advanced analytics or even launching their own satellites. Descartes Lab, a spin off of internal research project at Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) in New Mexico, was founded in 2014 and started off with open Landsat and MODIS data. They built a powerful cloud-based platform to analyze open EO data using machine learning. Early use cases included agriculture yield forecasting, forest monitoring, and commodity market analysis. They still list some of these open data set as core datasets on their platform.

A final and crucial lesson is the role of public innovation funding in nurturing early-stage EO startups and research capacity. While training programs are valuable for building technical skills across the continent, they often fall short when there are no viable markets or funding pathways to apply those skills. As a result, Africa continues to lose talent to regions where innovation ecosystems are better supported. To change this, African governments and regional institutions could establish dedicated EO innovation funds to support local startups and entrepreneurs, invest in locally driven research, pilots, and prototypes that reflect African priorities and contexts. Targeted funding even at small scales can unlock big value.

Building on African Foundations

Fortunately, Africa already has meaningful momentum. At the continental level, the African Union (AU) serves as the strategic umbrella under which several critical EO initiatives have been launched to support Africa’s development agenda. Through its leadership in space policy and its role in shaping Agenda 2063, the AU has been instrumental in enabling programs like GMES & Africa, EO AFRICA and AfSA. Together, these initiatives embody the AU’s vision of leveraging space science and Earth Observation as enablers of economic transformation and sustainable development across the continent.

GMES & Africa is focused on delivering operational EO services across thematic areas like water, agriculture, marine resources, and disaster management and has built capacity in regional centers.

Adding a critical innovation and research dimension is EO AFRICA. EO AFRICA’s long-term vision is to foster African-led innovation and research in Earth Observation. Through its R&D Facility, the initiative supports African–European research tandems, offers access to a cloud-based Innovation Lab for data processing, and provides training through the Space Academy. This initiative is essential for building a new generation of African EO researchers, innovators, and developers who can use satellite technology to solve real-world problems.

AfSA was establised in 2018 to drive Africa's ambition in space and technology. It serves as a central institution to guide, advocate, and coordinate the integration of space technologies into Africa’s broader development goals.

Crucially, these programs align with the broader ambitions outlined in the African Space Strategy report. This strategy positions space science and technology — including Earth Observation — as a cornerstone for achieving Agenda 2063, the AU’s 'blueprint for transforming Africa into a global powerhouse'. The strategy emphasizes that EO and space applications contribute directly to over 90% of the AU’s strategic objectives in agriculture, environmental monitoring, climate resilience, natural disaster management, public health, defense, and more.

However, to fully capitalize on their impact, the next step is clear, these efforts must be better connected to market mechanisms and national procurement frameworks that create sustainable demand for EO-based services across sectors. What’s needed now is to strengthen the link between this public infrastructure and the commercial market, enabling local startups, SMEs, and innovators to build viable EO businesses that address Africa’s unique challenges and opportunities.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the commercial EO sector in these economies were enabled. It is now clear that government support remains the most critical determinant in building a successful commercial Earth Observation (EO) ecosystem. While policy lays the foundation, the work doesn’t stop there. Narrowing the knowledge gap between technical capabilities and policy implementation will be essential for positioning EO as a strategic development tool across Africa especially for private sector investment.

This calls for a collective responsibility to help decision-makers understand not just what EO can do, but why it matters. We now have the benefit of hindsight.

Additional References

- A Political History Of U.S. Commercial Remote Sensing

- Satellite based commercial EO industry: Time to get down to business

- Enhancedview programme: Intelligent imagerys

- How Earth Observation became Europe's Sillicon Valley

Additional Notes

"Publishing a theory should not be the end of one’s conversation with the universe but the beginning." This quote is my guiding light and I often update this section with new information.

- Before 1994, it was possible for private companies in the U.S. to operate Earth Observation satellites, but only at relatively low resolutions(generally no better than 30 meters) for national security reasons.

- The European Comission launched the CASSINI Space Entrepreneurship Initiative in 2021 to boost the EU space sector, particularly through support for startups and SMEs. CASSINI provides access to funding, business acceleration, matchmaking, and investment opportunities through instruments like the Cassini Hackathons, Business Accelerator, and the Cassini Seed and Growth Funding Facility.